Zapruder film

The Zapruder film is a silent 8mm color motion picture sequence shot by Abraham Zapruder with a Bell & Howell home-movie camera, as United States President John F. Kennedy's motorcade passed through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. Unexpectedly, it captured the President's assassination.

Although it is not the only film of the shooting, the Zapruder film has been described as being the most complete, giving a relatively clear view from a somewhat elevated position on the side from which the president's fatal head wound is visible. It was an important piece of evidence before the Warren Commission hearings, and all subsequent investigations of the assassination. It is one of the most studied pieces of film in history, particularly footage of the final shot which helped spawn theories of whether Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone assassin.

In 1994, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Creation

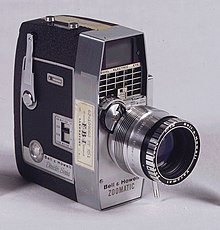

[edit]Abraham Zapruder stood on a concrete pedestal along Elm Street in Dealey Plaza holding a Model 414 PD Bell & Howell Zoomatic Director Series Camera. He filmed from the time the presidential limousine turned onto Elm Street[1] for a total of 26.6 seconds, exposing 486 frames of standard 8 mm Kodachrome II safety film, running at an average of 18.3 frames/second.[note 1]

After Secret Service agent Forrest Sorrels promised Zapruder that the film would only be used for an official investigation, the two men sought to develop the footage as soon as possible. As television station WFAA's equipment was incompatible with the format, Eastman Kodak's Dallas film processing facility developed the film and Jamieson Film Company produced three copies. Zapruder gave two of the copies to Sorrels and they were sent to Washington. The original film was retained by Zapruder, in addition to one of the copies.[1]

On the morning of November 23, 1963, CBS lost the bidding for the footage to Life magazine's $150,000 offer ($1,490,000 in 2025).[4] CBS News correspondent Dan Rather was the first to report on the footage on national television after seeing it. The inaccuracies in his description contributed to many conspiracy theories about the assassination.[1] In his 2001 book Tell Me a Story, CBS producer Don Hewitt said that he told Rather to go to Zapruder's home to "sock him in the jaw", take the film, copy it, then return it and let the network's lawyers deal with the consequences. According to Hewitt, he realized his mistake after ending their telephone conversation and immediately called Rather back to countermand the order, disappointing the reporter.[5][6] In a 2015 interview on Opie with Jim Norton, Rather stated that the story was a myth.[7]

Frame 313 of the film captures the fatal shot to the President's head. After claiming to have a nightmare in which he saw a sign in Times Square, New York City, with the phrase "See the President's head explode!", Zapruder insisted that frame 313 be excluded from publication.[1] The November 29, 1963 issue of Life published about 30 frames of the Zapruder film in black and white. Frames were also published in color in the December 6, 1963 special "John F. Kennedy Memorial Edition", and in issues dated October 2, 1964 (a special article on the film and the Warren Commission report), November 25, 1966, and November 24, 1967.[citation needed]

Zapruder was one of at least 32 people in Dealey Plaza known to have made film or still photographs at or around the time of the shooting.[8]

Subsequent history

[edit]The Zapruder film frames that were used by the Warren Commission were published in black and white as Commission Exhibit 885 in volume XVIII of the Hearings and Exhibits.[9] Copies of the complete film are available on the Internet.[10][11][12][13][14][15] One of the first-generation Secret Service copies was loaned to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in Washington, D.C., which made a second-generation copy.[16] After studies of that copy were made in January 1964, the Warren Commission judged the quality to be inadequate, and requested the original film. Life brought the original to Washington in February for the commission's viewing, and made color 35mm slide enlargements from the relevant frames of the original film for the FBI. From those slides, the FBI made a series of black-and-white prints, which were given to the commission for its use.[16]

In October 1964, the U.S. Government Printing Office released 26 volumes of testimony and evidence compiled by the Warren Commission. Volume 18 of the commission's hearings reproduced 158 frames from the Zapruder film in black and white. Frames 208–211 were missing, a splice was visible in frames 207 and 212, frames 314 and 315 were switched around, and frame 284 was a repeat of 283.[17] In response to an inquiry, then-FBI director J. Edgar Hoover wrote in 1965 that frames 314 and 315 had been swapped due to a printing error, and that that error did not exist in the original Warren Commission exhibits.[18]

In early 1967, Life released a statement saying that four frames of the original (frames 208–211) were accidentally destroyed, and the adjacent frames damaged, by a Life photo lab technician on November 23, 1963. Life released those missing frames from the first-generation copy it had received from the film's original version.[19] The Zapruder frames outside the section used in the commission's exhibits, frames 155–157 and 341, were also damaged and were spliced out of the original rendition of the film, but are present in the first-generation copies.[20]

In 1966, assassination researcher Josiah Thompson, while working for Life, was brought in to examine a first-generation copy of the film and a set of color 35mm slides made from the original. He tried negotiating with Life for the rights to print important individual frames in his book Six Seconds in Dallas. Life refused to approve the use of any of the frames, even after Thompson offered to give all profits from the book sales to Life. Following its publishing in 1967, Thompson's book featured some very detailed charcoal drawings of important individual frames, plus photo reproductions of the four missing ones. Time Inc. filed a lawsuit against Thompson and his publishing company for copyright infringement.[21]

A U.S. District Court ruled in 1968 that the Time Inc. copyright of the Zapruder film was not violated by invoking the doctrine of fair use. The court held that "there is a public interest in having the fullest information available on the murder of President Kennedy, saying that Thompson "did serious work on the subject and has a theory entitled to public consideration" and that "the copying by defendants was fair and reasonable."[22]

In 1967, Life hired New Jersey film lab Manhattan Effects to make a 16 mm film copy of the Zapruder film's original version. Pleased with the results, they asked for a 35 mm internegative to be made. Mo Weitzman made several internegatives in 1968, giving the best to Life and retaining the test copies. Weitzman set up his own optical house and motion-picture postproduction facility later that year. Hired in 1969, employee and assassination buff Robert Groden used one of Weitzman's copies and an optical printer to make versions of the Zapruder film with close-ups and minimize the shakiness of Zapruder's camera.[23]

Before the 1969 trial of Clay Shaw, a businessman from New Orleans, for conspiracy in connection with the assassination, a copy of the film made several generations from the original was subpoenaed from Time Inc. in 1967 by New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison for use at Shaw's grand jury hearing. Garrison unsuccessfully subpoenaed the original film in 1968. The courtroom showings of Garrison's copy in 1969 were the first time it had been shown in public as a film. Garrison allowed copies of the film to be made and these low quality copies began circulating among assassination researchers and were known to many journalists as well.[24] Zapruder's film was aired as part of a Los Angeles area television newscast on February 14, 1969.[25]

The first broadcast of the Zapruder film was on the late-night television show Underground News with Chuck Collins, originating on WSNS-TV, Ch 44, Chicago in 1970. It was given to director Howie Samuelsohn by Penn Jones and later aired in syndication to Philadelphia, Detroit, Kansas City, and St. Louis.[26]

On March 6, 1975, on the ABC late-night television show Good Night America, hosted by Geraldo Rivera, assassination researchers Robert Groden and Dick Gregory presented the first-ever US network television showing of the Zapruder film. The public's response and outrage to that television showing quickly led to the forming of the Hart-Schweiker investigation, which contributed to the Church Committee Investigation on Intelligence Activities by the United States, and resulted in the House Select Committee on Assassinations investigation.[27]

In April 1975, in settlement of a royalties suit between Time Inc. and Zapruder's heirs that arose from the ABC showing, Time Inc. sold the film's initial rendition and its copyright back to the Zapruder family for the token sum of $1. Time Inc. wanted to donate the film to the U.S. government. The Zapruder family originally refused to consent. In 1978, the family transferred the film to the National Archives and Records Administration for appropriate preservation and safe-keeping, while still retaining ownership of the film and its copyright. Director Oliver Stone paid over $85,000 to the Zapruder family for use of the Zapruder film in his motion picture JFK (1991).[24]

On October 26, 1992, then-U.S. President George H. W. Bush signed into law the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act (the "JFK Act"), which sought to preserve for historical and governmental purposes all records related to President Kennedy's assassination. The Act created the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection at the National Archives. The Zapruder film was automatically designated an "assassination record" and therefore became the official property of the United States government.[28]

On April 24, 1997, the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB), which the JFK Act created, announced a "Statement of Policy and Intent with Regard to the Zapruder Film". The ARRB re-affirmed that the Zapruder film was an "assassination record" within the JFK Act's meaning and directed it to be transferred on August 1, 1998, from its present-day location in NARA's film collection to the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection maintained by NARA.[note 2] As required by the US federal law for such a seizure under eminent domain, payment to Zapruder's heirs was attempted. Because the film is unique, its value was difficult to ascertain. Eventually, following arbitration with the Zapruder heirs, the government purchased the film in 1999 for $16 million. At that time, the family retained copyright to the film.[28]

In December 1999, the Zapruder family donated the film's copyright to the Sixth Floor Museum, in the Texas School Book Depository building at Dealey Plaza, along with one of the first-generation copies made on November 22, 1963, and other copies of the film and frame enlargements once held by Life magazine, which had since been returned.[29]

The film's relevant history is covered in a 2003 David R. Wrone book entitled The Zapruder Film: Reframing JFK's Assassination. Wrone is a history professor who tracks the chain of evidence for the film.[30]

Study of the film

[edit]This section about the study of the film relies excessively on references to primary sources. (May 2015) |

Every frame of the Zapruder film has been put together into a panoramic movie. Each object that appears during the film has its starting position equal to where it appears first in its frames. The objects' positions are updated during visibility in the Zapruder frames, and they stay motionless once each object moves out of those frames.[31]

The Orville Nix film had the same technology applied to it. The Nix and Zapruder films were then combined into a direct simultaneous comparison movie.[32]

Between November 1963 and January 1964, the FBI examined a copy of the Zapruder film, noting that the camera recorded at an average of 18.3 frames per second. It is not clear from the film itself as to when the first and second shots occurred. It is apparent that by frame 225 the President is reacting to his throat wound. However, no wound or blood is seen on either President Kennedy or Governor Connally prior to frame 313.[citation needed]

Dispute over authenticity

[edit]The view that the Zapruder film captured the shooting from beginning to end was challenged by Max Holland, author of The Kennedy Assassination Tapes, and professional photographer Johann Rush in a joint editorial piece published by The New York Times on November 22, 2007.[33] Holland and Rush have pointed out that Zapruder temporarily stopped filming at around frame 132, when only police motorcycles were visible. When he continued filming, frame 133 already shows the presidential motorcade in view. Holland and Rush suggest that the pause could have had great significance for the interpretation of the assassination.[citation needed]

One of the sources of controversy with the Warren Report is its difficulty in satisfactorily accounting for the sequencing of the assassination. A specific mystery concerns what happened to the one shot that missed, and how Lee Harvey Oswald came to miss at what was assumed to be close range. Holland and Rush argue that the break in the Zapruder film might conceal a first shot earlier than analysts have hitherto assumed, and point out that in this case, a horizontal traffic mast would temporarily have obstructed Oswald's view of his target. In the authors' words, "The film, we realize, does not depict an assassination about to commence. It shows one that had already started."[34]

The evidence offered by Holland and Rush to support their theory was challenged in a series of 2007–08 articles by computer animator Dale K. Myers and assassination researcher Todd W. Vaughan, who defended the prevailing belief that Zapruder's film captured the entire shooting sequence.[35]

The authenticity of the image in frame 313 was challenged by Douglas Horne, Senior Analyst for the Assassination Records Review Board and Dino Brugioni of the CIA's National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC). Brugioni was considered the world's foremost imagery intelligence analyst until his death in 2015.[36] Horne discovered the NPIC worked on two different versions of the Zapruder film on Saturday and Sunday nights immediately following the assassination, which had occurred on Friday.[37]

The work was done by separate teams that had been compartmentalized and ordered not to speak of their work, causing the teams not to know about each other, even though the personnel from the two teams normally worked together on a daily basis. When Horne showed his findings and evidence to Brugioni, the latter re-examined a copy of the extant Zapruder film, provided by Horne.[38] Brugioni then stated the Zapruder film in the National Archives today, and available to the public, specifically frame 313, is an altered version of the film he saw and worked with on November 23–24, the earlier of the two versions handled by the NPIC.[37]

Brugioni recalled seeing a "white cloud" of brain matter, three or four feet (91 or 122 cm) above Kennedy's head, and said that this "spray" lasted for more than one frame of the film. The version of the Zapruder film available to the public depicts the fatal head shot on only one frame of the film, frame 313. Brugioni was certain that the set of briefing boards available to the public in the National Archives is not the set that he and his team produced on November 23–24, 1963.[39][40]

The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza denies that the Zapruder film has been altered, or that any of the frames are missing from the film.[41] Kodak engineer Ronald Zavada ran experiments with the film Abraham Zapruder used and concluded that the film is authentic.[42]

Cultural effect

[edit]In 1994, the Zapruder film footage was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and was selected for permanent preservation in the National Film Registry.[43]

Some critics have stated that the violence and shock of this home movie led to a new way of representing violence in 1970s American cinema, both in mainstream films, and particularly in indie and underground horror movies.[44][45]

The film has been featured in films and other media, such as the Oliver Stone film JFK. A closeup from the portion of the film showing the fatal shot to Kennedy's head is also shown in the Clint Eastwood film In the Line of Fire.[46]

Abraham Zapruder is sometimes presented as a forefather of all citizen journalists.[47]

In "Murder Most Foul", a musical meditation on Kennedy's assassination and its effect on American counterculture, Bob Dylan sings "Zapruder's film I've seen that before / seen it 33 times maybe more".[48]

The video was projected onto Lee Harvey Oswald's T-shirt in the 2004 revival of the Broadway musical Assassins.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The Model 414 PD held a reel of 16 mm film which was first run in one direction, with half of the width of the film being exposed. The reel would then be removed from the camera (a process which could take place in subdued light), the feed and take-up reels swapped and reloaded so that the other half of the film could be exposed in a process analogous to half-track audio tape. The FBI later tested Zapruder's camera and found that it filmed an average of 18.3 frames/second (slightly deviating from the camera's standard frame rate of 16 frame/s).[2] While earlier 8 mm cameras had used a 16 frame/s rate, the 8 mm standard was moving to 18 frame/s by the 1960s, and that was the frame rate adopted by the Super 8 format in 1966.

- ^ The film's physical location remained the same, only its record classification changed.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Pasternack, Alex (November 23, 2012). "The Other Shooter: The Saddest and Most Expensive 26 Seconds of Amateur Film Ever Made". Motherboard. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ Richard B. Trask, Photographic Memory: The Kennedy Assassination, November 22, 1963, Dallas: Sixth Floor Museum, 1996, p. 5.

- ^ Huey, Pamela (November 20, 2013), "Jackie's Secret Service agent tells what he saw, did", The Buffalo News, retrieved May 17, 2024

- ^ "Kennedy's Assassination: How LIFE Brought the Zapruder Film to Light". LIFE.com. October 24, 2013. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Kaiser, Charles (April 2, 2001). "World's Oldest Cub Reporter: Hewitt's Half Century at CBS". New York Observer. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Hewitt, Don (2002) [2001]. "New Frontiers". Tell Me A Story: 50 Years and 60 Minutes in Television. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 81. ISBN 9781586489656. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016.

- ^ Gregg Hughes and Jim Norton (October 30, 2015). "Dan Rather Seeing the Zapruder Film". www.youtube.com (Podcast). Opie Radio. Event occurs at 3:28–4:04. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Vincent Bugliosi, Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. W.W. Norton, 2007, endnotes, p. 291.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings and Exhibits, Vol. XVIII Archived December 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Online version at the History Matters Archive.

- ^ Zapruder Film of JFK Assassination on YouTube.

- ^ Stabilized Version of the Zapruder Film on YouTube.

- ^ Stabilized versions of the Zapruder film Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Research quality. Based on the "Costella 2006" frames. Large file sizes. Requires QuickTime viewer from apple.com. Entire film is covered in six "fixed camera" video clips, plus one "stabilized pan" video clip. Full speed.

- ^ JFK Kennedy shooting, Zapruder audiovideo on YouTube. Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione. The Zapruder film has been added to the sound recorded by police in Dallas.

- ^ All 486 frames of the Zapruder film Archived September 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The "Costella 2006" frames. Research quality. Does not require special viewers, but not shown in movie form.

- ^ John P. Costella, "The New Zapruder Film", Assassination Research, Vol.2 No.2 (2003) Archived May 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Stabilized version which allows frame-by-frame easy forward.

- ^ a b Vincent Bugliosi (2007). Reclaiming history: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-393-04525-3. Archived from the original on November 22, 2023. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Frames 207 and 212 Archived December 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, frames 283 and 284 (actually 283) Archived December 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, frame 314 (actually 315) Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, and frame 315 (actually 314) Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Life To Release Today Part of Kennedy Film", New York Times, January 30, 1967, p. 22;

- ^ "Life To Release Today Part of Kennedy Film", New York Times, January 30, 1967, p. 22;

- ^ Vincent Bugliosi (2007). Reclaiming history: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 504–505. ISBN 978-0-393-04525-3. Archived from the original on November 22, 2023. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Time Inc. v. Bernard Geis Associates, 293 F.Supp. 130, 146 (D.C.N.Y. 1968).

- ^ Time Inc. v. Bernard Geis Associates, 293 F.Supp. 130, 146 (D.C.N.Y. 1968).

- ^ Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board. Assassination Records Review Board. 1998. pp. 138–139. ISBN 9780160497629. Archived from the original on November 22, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Frye, Brian L. (May 29, 2017). "Zapruder Film [Chapter 34]". In Op den Kamp, Claudy; Hunter, Dan (eds.). A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on November 22, 2023. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ "Abraham Zapruder Film | The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza". www.jfk.org. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ Zapruder, Alexandra (2016). Twenty-Six Seconds: A Personal History of the Zapruder Film (E-book ed.). Grand Central Publishing.

One of these showings was on the late-night television program Underground News with Chuck Collins

- ^ Vincent Bugliosi (2007). Reclaiming history: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-393-04525-3. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ a b "Zapruder Heirs to Get $16M for Film". Washington Post. Associated Press. August 3, 1999. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Zapruder Film Press Release Archived October 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, January 18, 2000. The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza.

- ^ MacDonald, DW (2005). "Book Review. The Zapruder Film: Reframing JFK's Assassination by David R. Wrone". Critical Criminology. 13: 239. doi:10.1007/s10612-004-6109-3. S2CID 189953124 – via Ebsco.

- ^ JFK Assassination Zapruder Stabilized Motion Panorama HD plus SloMo – 50th anniversary on YouTube

- ^ JFK Assassination Stabilized Motion Panorama HD Nix v Zapruder – 50th anniversary (HD) on YouTube

- ^ Holland, Max; Rush, Johann (November 22, 2007). "J.F.K.'s Death, Re-Framed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018.

- ^ The Truth Behind JFK's Assassination Archived February 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, by Max Holland, Newsweek, November 20, 2014.

- ^ Myers, Dale K. (June 25, 2007). "JFK Files: Max Holland's 11 Seconds in Dallas". jfkfiles.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ Klein, Larry (September 2002). "NOVA | Spies That Fly | Master of the Surveillance Image | PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on November 22, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ a b P., Horne, Douglas (2009). Inside the Assassination Records Review Board : the U.S. government's final attempt to reconcile the conflicting medical evidence in the assassination of JFK. [Falls Church, VA.] ISBN 9780984314409. OCLC 596184454.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Horne, Douglas (January 11, 2014). "The Zapruder Film Mystery". Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "The Zapruder Film Mystery Archived November 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine", YouTube, published on August 15, 2014

- ^ Janney, Peter (October 2016) [2013]. Mary's Mosaic: The CIA Conspiracy to Murder John F. Kennedy, Mary Pinchot Meyer, and Their Vision for World Peace (3 ed.). New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. p. 292. ISBN 978-1-51070-8921.

- ^ "Zapruder FAQ". Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ Lahman, Sean (November 22, 2013). "Zapruder film analysis still disputed". USA Today/Rochester (N.Y.) Democrat and Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "25 Films Added to National Registry". The New York Times. November 15, 1994. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ World Archipelago. "Wallflower Press" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2006.

- ^ (in French) 26 secondes: L'Amérique éclaboussée. Archived October 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Review (August 23, 2012). "IN THE LINE OF FIRE Review". Movieguide | The Family Guide to Movies & Entertainment. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "La mort de JFK dans le viseur de Zapruder" [JFK's death in Zapruder's sights] (in French). Archived from the original on August 29, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ "Murder Most Foul | The Official Bob Dylan Site". www.bobdylan.com. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Moving Images Relating to the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, 1992–1998 at the National Archives and Records Administration

- The History of the Zapruder Film Archived March 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- The Zapruder Camera Bell & Howell 414PD Director Series – Overview and User's Manual.

- Zapruder Film of Kennedy Assassination at IMDb

- 1963 films

- 1963 short films

- Films about the assassination of John F. Kennedy

- United States National Film Registry films

- American silent short films

- Amateur filmmaking

- Filmed assassinations

- Filmed killings in North America

- Films shot in Dallas

- One-shot short films

- 1960s American films

- Surviving American silent films